This post started life as an invited paper for VALA2018: Libraries, Technology, and the Future (Melbourne, 13-15 February 2018). If you would rather see that, the video and slides are available online here.

A thin veneer of immediate reality is spread over nature and artificial matter, and whoever wishes to remain in the now, with the now, on the now, should please not break its tension film. Otherwise the inexperienced miracle-worker will find himself no longer walking on water but descending upright among staring fish (Vladimir Nabokov, 1972)

In his short novel Transparent Things (1972) Nabokov suggests that, unless we are careful, we sink into the history of things. Remaining fully in the present is difficult; it takes effort not to slip into reflection, memories, and the past.

But in the museums and collections space things can often prove more resistant. I have written here before about the bookseller William Hutton and his visit to the British Museum in 1784. It ended with him grieving over how much he lost “for want of a little information.” When preparing the influential anthology The New Museology Peter Vergo also cited Hutton (‘The Reticent Object,’ 1989) as part of a call for effective contextualisation.

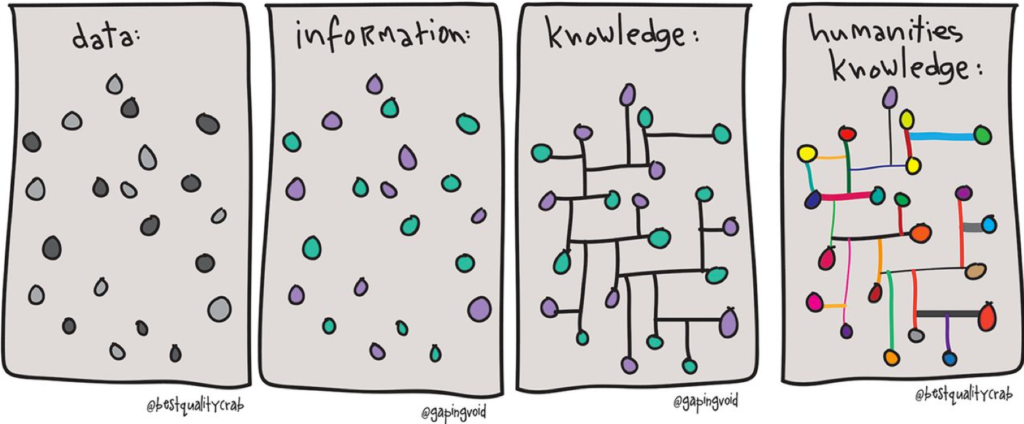

Museum literature from the two hundred years between is littered with similar sentiments. We need additional knowledge and support beyond just the object or the record itself to understand and engage with many collection items. And, while curated exhibition spaces have come a long way in addressing these issues, collections data is now increasingly published online, creating the need for expanded collections documentation.

One means for linking items to a broader context is through hierarchical classification. This places like with like, grouping items into categories which are in turn placed within larger categories. These information structures are often represented as trees – a mode of visualisation which can be traced back at least 800 years (Lima, 2014).

Ernst Haeckel, Tree of Life (1866)

While perhaps most familiar from the natural sciences, taxonomic hierarchies are also used elsewhere. At the VALA2018 conference keynote speaker Natasha McEnroe showed an image of the NeXTcube computer used by Tim Berners-Lee to design the World Wide Web at CERN in 1990, now held at London’s Science Museum. There in the metadata is a hierarchical taxonomy: furnishing and equipment > tools & equipment > computer.

The tree metaphor has been the subject of critique for some time. In his 1948 article ‘The Nature of Culture,’ Alfred L. Kroeber writes:

the course of organic evolution can be portrayed properly as a tree of life, as Darwin has called it, with trunk, limbs, branches, and twigs. The course of development of human culture in history cannot be so described, even metaphorically. There is a constant branching-out, but the branches also grow together again, wholly or partially, all the time. Culture diverges, but it syncretizes and anastomoses too.

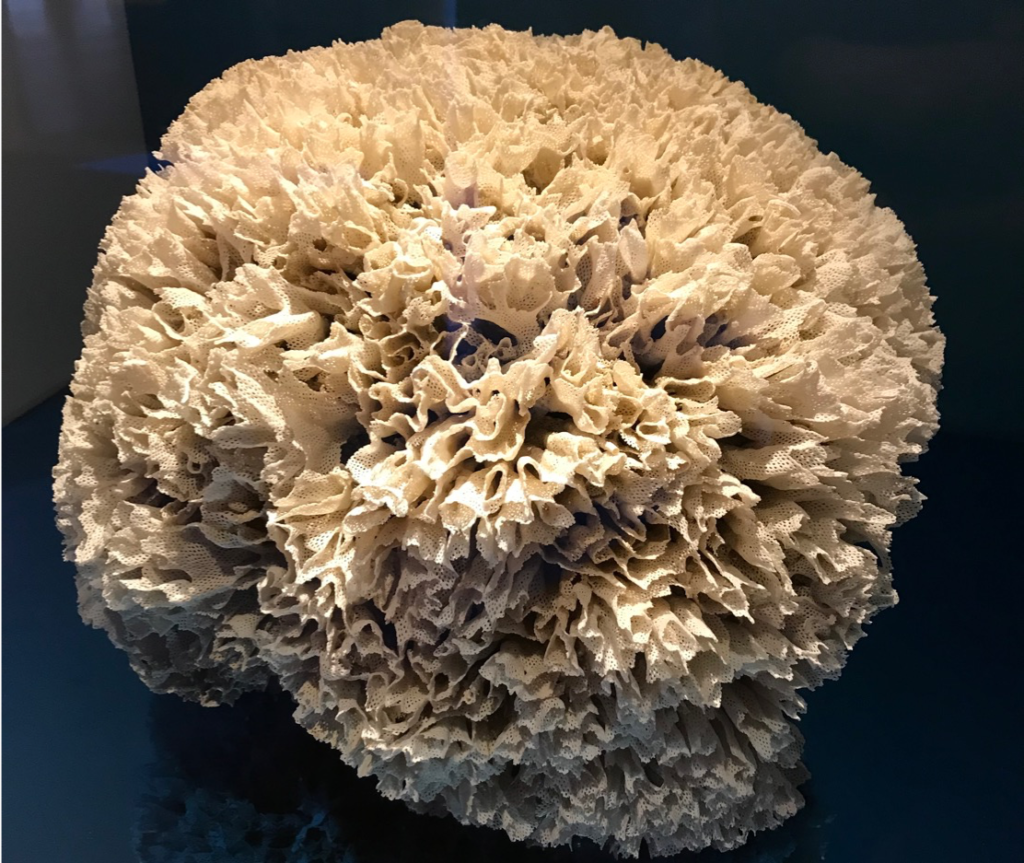

Later Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari presented “arborescent systems” as an example of old modes of thought that “grant all power to a memory or central organ” (1980/2013). Where Deleuze and Guattari look underground to the rhizome for an alternative, Kroeber looks underwater, to the coral reef.

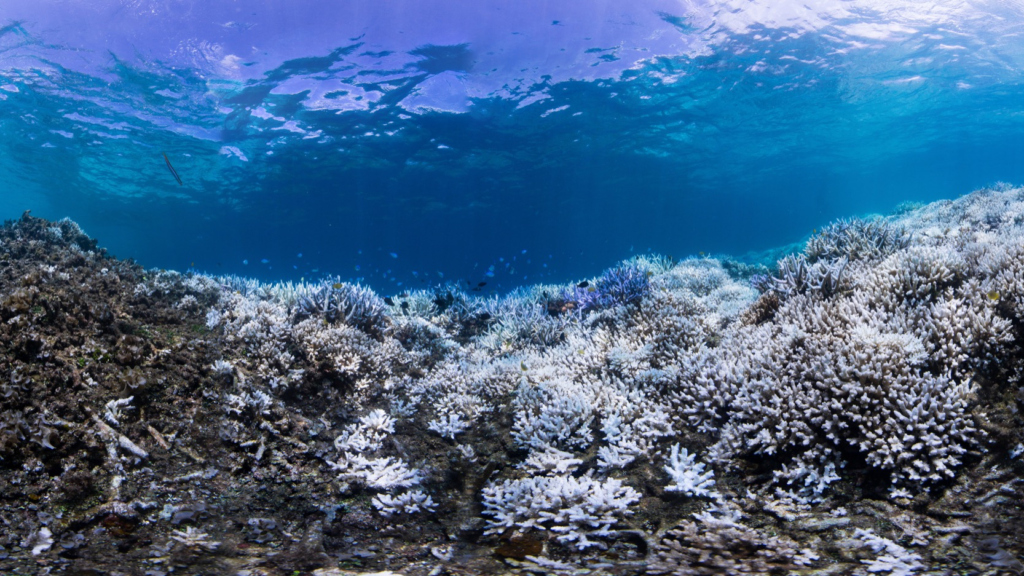

Here there are still hierarchies; but other structures exist too. It is a world of accumulations and accretions, of interconnections and complex systems where the interaction of animals, plants, and minerals are evidenced in the calcified leavings that build up over time, and which can later be read like the rings of a tree.

Donna Haraway explores the metaphor of the reef when introducing a collection of interviews:

the layered conversations of patterned interviews among interlocutors who are distributed in time, space, linguistic commitments, and political yearnings mimic the complex communities of marine organisms, whose traffic in sustaining nutrients and meaningful signals tie dispersed members into unquiet webs of polyspecific, living tissue (1995)

The reef is a realm of individuals and plurality, of organisational groupings and structures built from calcified leavings. Things accumulate, syncretise, and accrete over timeframes comparable to human history, developing in zones which contain different types of organisms and activities, some more robust and lively than others, some which rarely see the light of day.

Visitors arrive frequently, a combination of locals and creatures from deeper water. Tourists skim the surface in glass-bottomed boats, while snorkellers come in for a closer look, and divers spend time exploring smaller sections in great detail, like the skimmers, swimmers, and divers mentioned by Nik Honeysett at Museums and the Web in Melbourne (2015), or an aquatic equivalent to the streakers, strollers, and students noted by museum director George F. MacDonald (1992).

Documentation and description can only do so much. As Sydney Hickson wrote in 1889:

A long list of the Latin names of the corals of a reef … conveys no impression even to many zoologists of the infinite variations of form, structure, and colour which those corals actually present in the living state; and the same might be said of the members of every other group of the animal kingdom. A coral reef cannot be properly described. It must be seen to be thoroughly appreciated.

So too with collections. The knowledge they contain is too varied and complex to be fully captured and encompassed in images, databases, and text. But we can do more than we currently are.

The word ‘context’ has its roots in the Latin term ‘contextus,’ which refers to weaving, joining, and connection. Osha Gray Davidson writes: “Coral reefs themselves, for all their complexity, are a single strand in a larger braid – a braid within a braid” (1998). The reef is ecological, rather than organismic or taxonomic. Davidson again: “Like taxonomists, ecologists are in the line-drawing business. The difference is that while taxonomists draw lines to separate organisms from each other, ecologists draw lines to connect them.”

We need to re-weave items into their context through the use of relationships, references, and connections – something I have written about here several times before:

• Two presentations in one (26 August 2016)

• Cross-references, keywords, and networks (4 October 2017)

• ‘Somehow a vital connection is made’ (12 November 2017)

The purpose here is not just to provide richer, more generous information to communities, researchers, and the general public; it is to develop systems which better capture, maintain, and make accessible the knowledge developed and utilised by curators, exhibition developers, and other collections users over time.

These connecting lines – drawn from evidence in the archives, personal filing systems, and the minds and memories of people within and far beyond the museum – are what make collections more conceptually similar to an ecological system than to an arborescent spread of categories containing discrete similar elements.

Like all complex systems, forming such structures requires energy, and entropy is a threat to their maintenance. Artist Robert Smithson defines the latter as the idea that “energy is more easily lost than obtained, and that in the ultimate future the whole universe will burn out and be transformed into an all-encompassing sameness” (1966). Knowledge, too, is more easily lost than obtained. Systems degrade, staff leave, files and notes are lost, bits rot, links break, and tools become obsolete, just as our reefs are under threat from run-off, negligence, pollution, lack of funding, and poor regulatory systems.

Collections-based knowledge is at risk if we focus on transitory public-facing systems at the expense of foundational institutional knowledge; if we allocate key funding to propping up legacy technologies or attempting to simply streamline or automate current recordkeeping and descriptive practice without first rethinking the ways in which we work; if we put all our energy into getting today’s visitor through the door without considering what protocols and practices we need to implement to sustain our knowledge into next year, next decade, or next century; if we fail to value the often submerged ecosystems of academic research, professional practice, and technological development which underpin so much of our tangible and intangible value.

When we fail to consider these things we risk losing a great deal, as over time the relationships and knowledge we need to ensure our collections remain discoverable, understandable, and usable will gradually leach away.

A mixture of bleached and dead corals around Okinawa, Japan, in September 2016.

Photograph: XL Catlin Seaview Survey

Thank you to Deb Verhoeven for her feedback on my VALA2018 talk, and all the conference attendees who asked questions and made comments. Your insights have all contributed to making this blog post a better piece.

References

Davidson, Osha Gray. The Enchanted Braid: Coming to Terms with Nature on the Coral Reef. New York: Wiley, 1998.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. Paperback edition. Bloomsbury Revelations. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013. (Original work published in 1980.)

Haraway, Donna. “Foreword.” In Women Writing Culture, edited by Gary A. Olson and Elizabeth Hirsh, xi–xiii. SUNY Series, Interruptions — Border Testimony(Ies) and Critical Discourse/S. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995.

Hickson, Sydney John. A Naturalist in North Celebes: A Narrative of Travels in Minahassa, the Sangir and Talaut Islands, with Notices of the Fauna, Flora and Ethnology of the Districts Visited. London: J. Murray, 1889. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/56606.

Honeysett, Nik. “Witchcraft.” MWA2015: Museums and the Web Asia 2015. Melbourne, Australia: Museums and the Web, 2015. https://mwa2015.museumsandtheweb.com/proposal/witchcraft/.

Hutton, William. “British Museum.” In A Journey from Birmingham to London, 186–97. Birmingham: Pearson and Rollason, 1785.

Kroeber, A. L. “The Nature of Culture [1948].” In Anthropology: Culture Patterns & Processes, 60–118. Asian Folklore and Social Life Monographs, v. 214. Taipei, Taiwan: Orient Cultural Service, 1994.

Lima, Manuel. Book of Trees: Visualizing Branches of Knowledge. New York, United States: Princeton Architectural Press, 2014.

MacDonald, George F. “Change and Challenge: Museums in the Information Society.” In Museums and Communities: The Politics of Public Culture, edited by Ivan Karp, Christine Mullen Kreamer, and Steven Lavine, 158–81. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992.

Nabokov, Vladimir. Transparent Things. London: Penguin Books, 2011.

Smithson, Robert. “Entropy and the New Monuments (1966).” In Robert Smithson, the Collected Writings, edited by Jack D. Flam, 10–23. Documents of Twentieth Century Art. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Vergo, Peter, ed. “The Reticent Object.” In The New Museology, 41–59. London: Reaktion Books, 1989.

Leave a Reply