On 7 July 1847, the Advertisements section of the Sydney Morning Herald invited operative plasterers to a meeting of the trade at the Redfern Inn to “consider the state (and contribute towards the relief) of the starving poor in Ireland and Scotland.” There were notices of meetings of the Bank of New South Wales and the Australian Floral and Horticultural Society, and William Thorn advised the inhabitants of the Goulburn that he could “supply innkeepers and private families with Ale and Porter, in any quantity, of the very best quality.”

Alongside these, a brief notice from Robert Lynd, Honorary Secretary of the Australian Museum: “The Public are respectfully informed that by the kindness of His Honor the Speaker, the cranium of the supposed Bunyip, recently discovered in the vicinity of Melbourne, may be inspected at the Australian Museum upon Wednesday and Thursday next, from ten to three o’clock.”

There were lots of tales about bunyips in the 19th century from across the south east of Australia. As part of my work with the Research Centre for Deep History (RCDH) at Australian National University, I’ve been exploring workflows for capturing and mapping historical stories like these as part of broader landscapes.

Though much of our research looks beyond colonial narratives, I wanted an example which would provide a useful set of published, publicly-accessible data for exploring digital workflows. This blog post looks at a few of my experiments, along with some considerations and identified challenges, and hopefully some useful links and references along the way.

The decision to work on bunyips was in part based on practical considerations. There is a lot of available content; the term is relatively easy to search for without needing much disambiguation (apart from references to the town of Bunyip, The Bunyip newspaper, and so on); and there have been several theories put forward as to the ‘true identity’ of the creature which provide opportunities for comparisons with existing datasets.

First I started a Zotero collection, assembling 96 references from the past 200 years (1823–2019) across a variety of media. Many of the early mentions were found via Trove’s digitised newspapers, but I also explored references in journals like The Tasmanian journal of natural science, agriculture, statistics, &c. (available via the Biodiversity Heritage Library), and in publications such as Godfrey Mundy’s Our Antipodes: Or, Residence and Rambles in the Australasian Colonies, with a Glimpse of the Goldfields (1852).

The intention here wasn’t to create a comprehensive set of material—more a representative sample of the sorts of sources available. I have made my 96 starting references available in an open Zotero group so feel free to jump in, have a browse, and if there are references you know of which you don’t see here (there are heaps missing!) feel free to add them. I would love to see a growing public collection of references about bunyips which anyone interested in the topic can draw on, rather than people starting from scratch every time. Historians don’t share their bibliographies enough.

Zotero is a great way to capture bibliographic data and digital versions of documents. But it’s not the best place to add context or non-bibliographic data. Among other things I wanted to start working with maps.

Since starting with RCDH I’ve been using Heurist as a tool for capturing rich contextual information and detailed relational data. Heurist also has relatively mature mapping functionality, and a simple Zotero import function. With a user ID, group ID, and API key (and a little fiddling with fields to make sure all the metadata you need has a destination) you can quickly pull a Zotero group into Heurist.

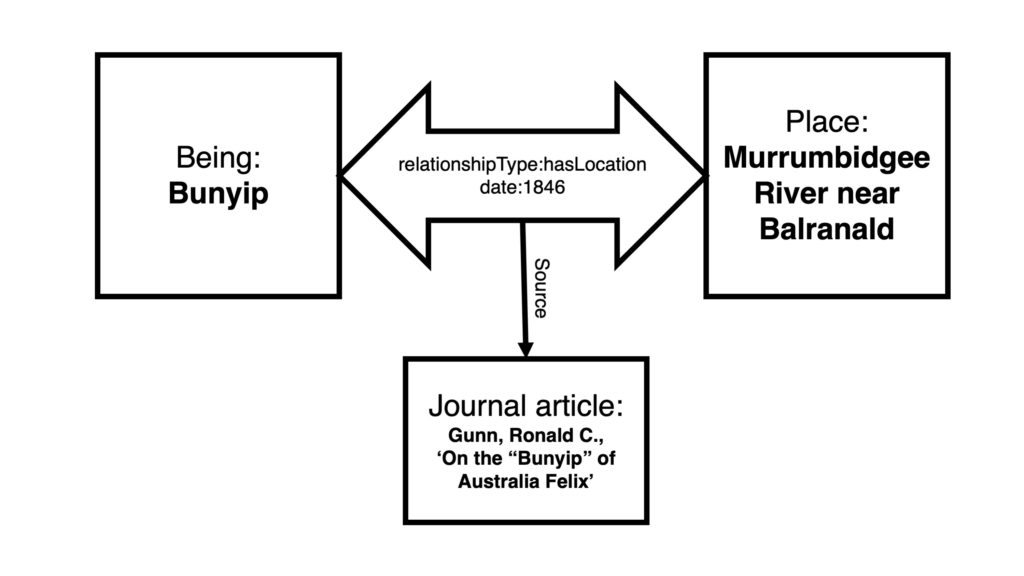

Heurist will create an entry for each bibliographic item, as well as people entities for authors, entries for journals and journal volumes, and so on. For example, Gunn, Ronald C. ‘On the “Bunyip” of Australia Felix’. The Tasmanian Journal of Natural Science, Agriculture, Statistics, &c. 3, no. 2 (1846): 147–49 results in four entities in Heurist:

- an entry for the journal article ‘On the “Bunyip” of Australia Felix’

- an entry for the journal volume (Vol. 3, No. 2, 1846) of The Tasmanian Journal of Natural Science, Agriculture, Statistics, &c.

- an entry for the journal The Tasmanian Journal of Natural Science, Agriculture, Statistics, &c.

- an entry for author Ronald C. Gunn

The pointers required to link these records together are also created by the system, e.g. the ‘Author’ field for the article points to the Ronald C. Gunn person entity, and the ‘Journal/volume’ field points to the journal volume entry.

Next I explored options for linking these articles to a geographic place. Finding coordinates is not a process that could easily be automated. Like a lot of heterogeneous historical data, the sources I am working with can be troublesome.

Some are poorly printed, which means OCR (optical character recognition) produces patchy results and requires a lot of cleanup. Even with cleaner data, processes like named-entity recognition would still not get me much closer to a location on a map. Some articles on bunyips contain historical place names which have not been used for decades. Others are vague (‘lower reaches of the Murrumbidgee’) or contain information like the name of a particular property or homestead which requires a degree of local knowledge. Others are historically specific, like an 1845 reference to ‘the very spot where the punt crosses the Barwon at South Geelong.’ Not something you will find on Google Maps.

Given all that, and the size of the dataset, I decided to do the work manually. Heurist makes it easy to select points on a map, or draw polygons to define a region. It also lets you include a degree of certainty (High confidence; Probable; Conjectural; Uncertain) which can be useful for historical data.

As someone interested in relational structures, I also wanted to think through how to link an article about bunyips to a particular place. If all I wanted to do was plot some points on a map the easiest option would be to simply create a list of places on a spreadsheet and add latitudes and longitudes. But I’m always keen to create a dataset which can potentially serve multiple purposes (mapping, network visualisations, websites, online collections, etc.). Pointing each article to a place in Heurist (Publication:Article A > Place:River X) would theoretically work, but I also wanted to take into account locations, claims, and evidence in a way which would prove useful for other sorts of analysis.

Therefore, rather than a pointer I introduced a ‘Being’ entity for the bunyip (useful when dealing with living entities that do not fit easily into categories like ‘People’ or ‘Animals’) and used a dated relationship entity to link this to a place at a particular date.

You will see here that the journal article is not related to the bunyip, or to the place, because it doesn’t actually tell us a lot that is useful about either; and even if it did, that’s not what I’m using it for here. The sources I am examining provide evidence for a relationship between the bunyip and a place at a particular point in time.

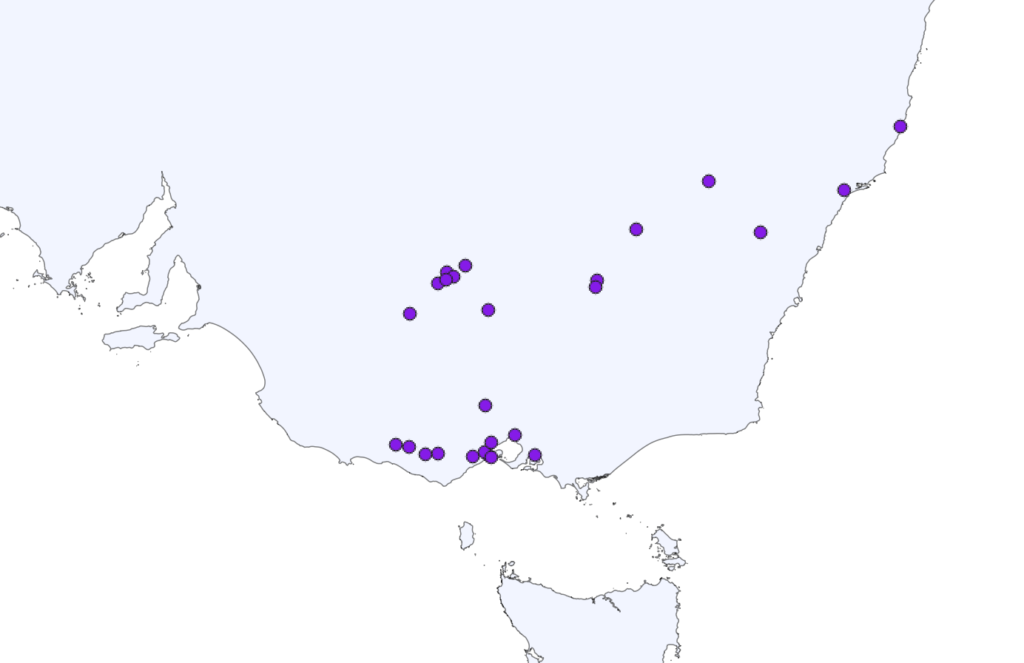

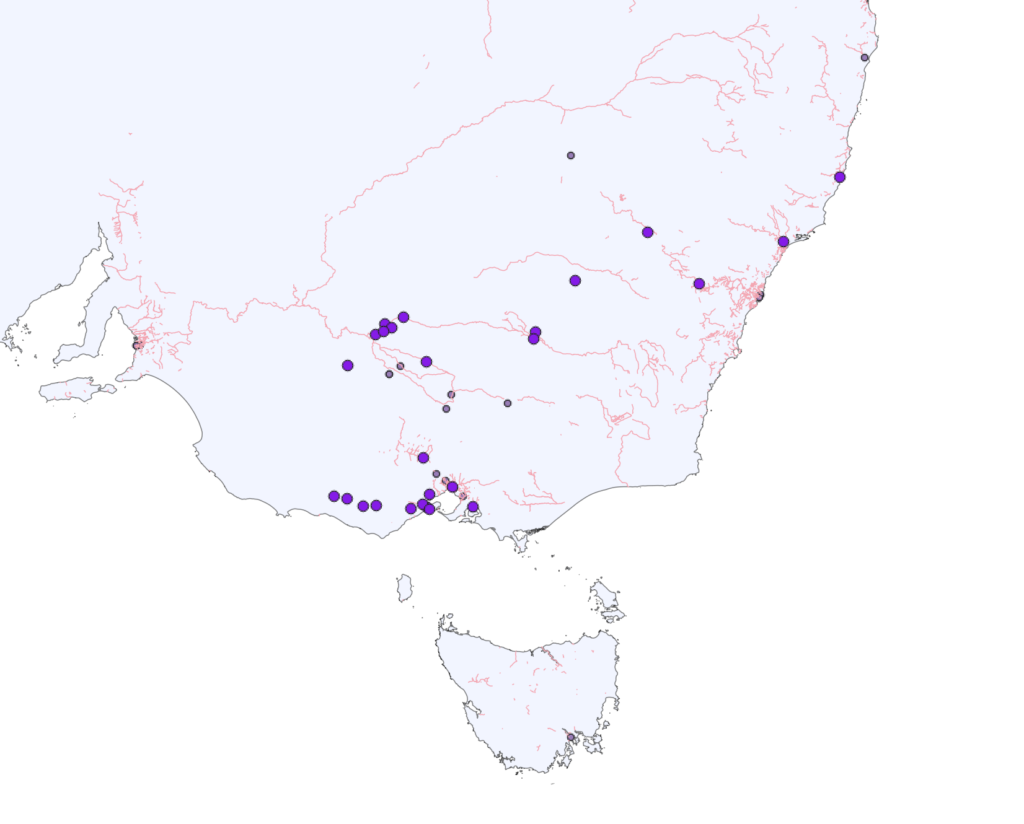

Though useful for other sorts of work, that complexity is then boiled off in the next step, which is a KML (Keyhole Markup Language) export from Heurist. Importing the 25 locations I have identifed so far into the free, open source mapping tool QGIS we get the following.

As you can see, all we have are points. A quick search online provides multiple shape files for Australia which, when imported, provide some useful geographic context.

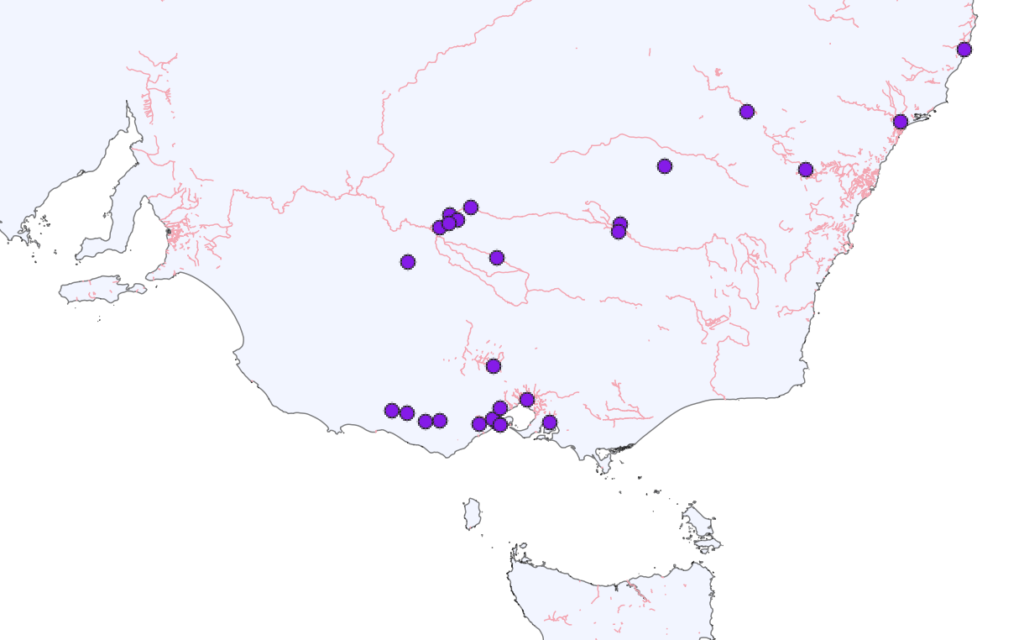

Bunyips are generally associated with water, so I also went searching for some decent free shapefiles for Australian waterways. I found one on mapcruzin.com but though it’s a start, it’s lacking in detail.

Many shape files like this are not well documented, with their contents presented as ahistorical observations rather than as snapshots filled with decisions, inclusions, and omissions at an (often unspecified) point in time. The danger here is that we end up with anachronistic maps overlaying historic data on more contemporary landscapes—which is exactly what I have produced here. Waterways change over time. Rivers can move (or be moved), waterholes change shape or dry up, dams and even lakes can be constructed, or drained. At longer timescales we see changing coastlines, rising and falling sea levels, deserts growing and contracting, and more. If we want to start using maps to ask more complex questions we need to develop more detailed, historically-focused shape files, and we need better dating, documentation, and provenance information for the ones we already have.

Despite these issues, as the whole map is partial and flattens time I will leave the waterways in place for now. Using this map as a base, next we can think about adding additional layers.

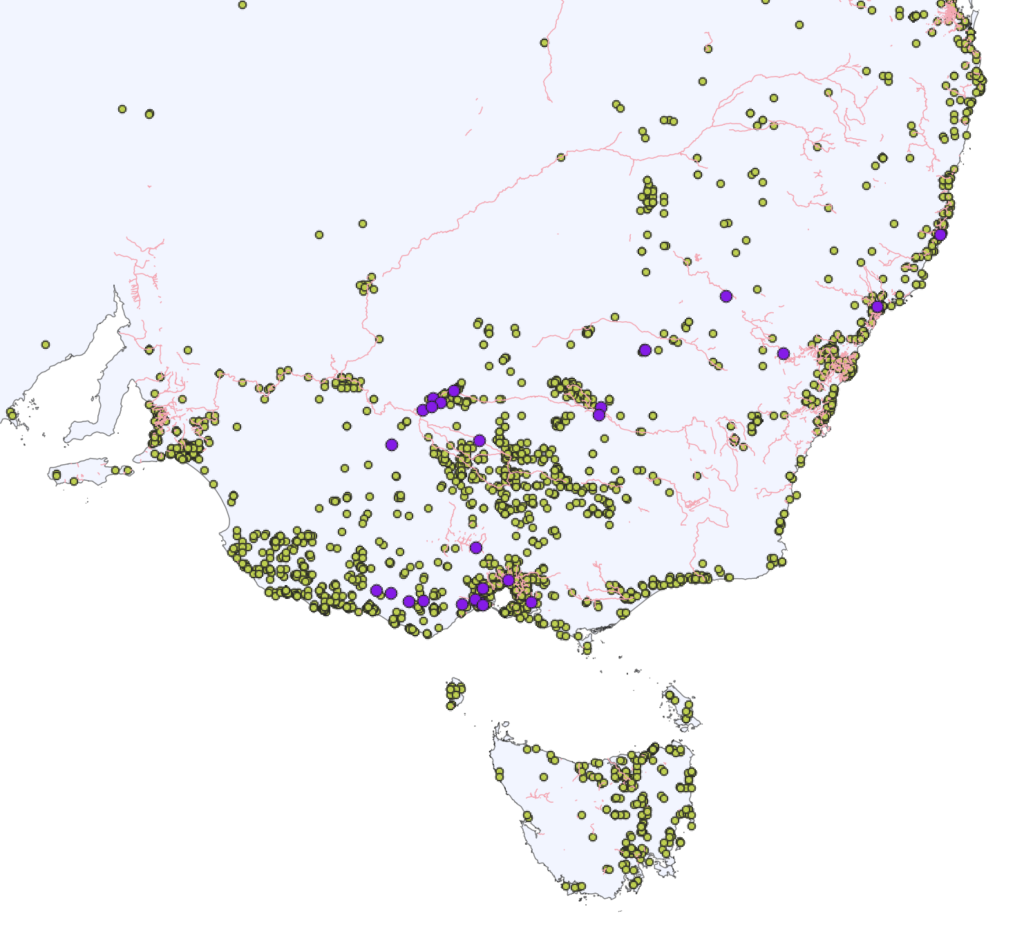

For example, some colonists believed the sound of the bunyip was actually the distinctive, booming call of the Australasian Bittern. Drawing on data from the Atlas of Living Australia (ALA), we can map in recorded sightings of the bittern from the 19th century, shown here as smaller dots.

This suggests that bittern sightings were not very widespread, perhaps contributing to the mystery surrounding its call, whereas if we bring in all the known sightings from ALA we see that the territories of the bittern and the bunyip overlap in many parts of the south-east.

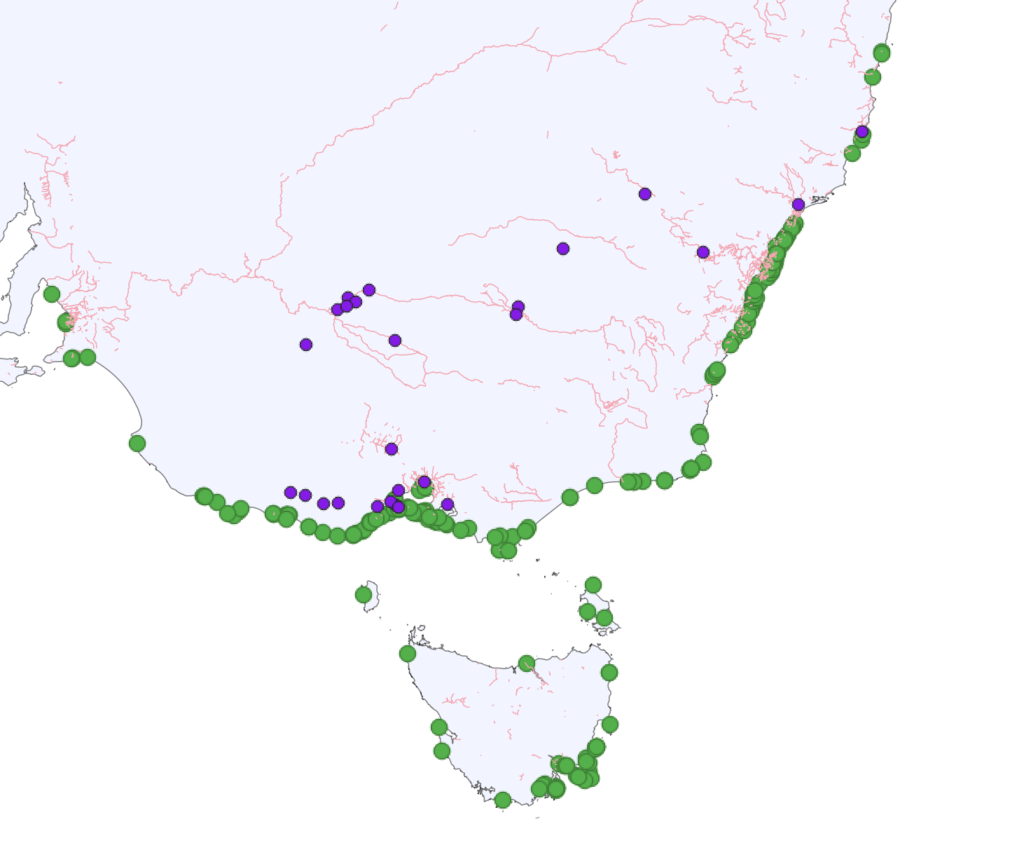

R. Brough Smyth’s Aborigines of Victoria (1878) notes another theory, that stories of a fierce beast in Australia’s waterways may have arisen due to encounters with leopard seals. But, at least according to ALA, there has never been an inland sighting of Hydrurga leptonyx.

While leopard seals on the southern coast may have led to cases of mistaken identity, it seems unlikely they would make it to the lower reaches of the Murrumbidgee without ever being observed and identified.

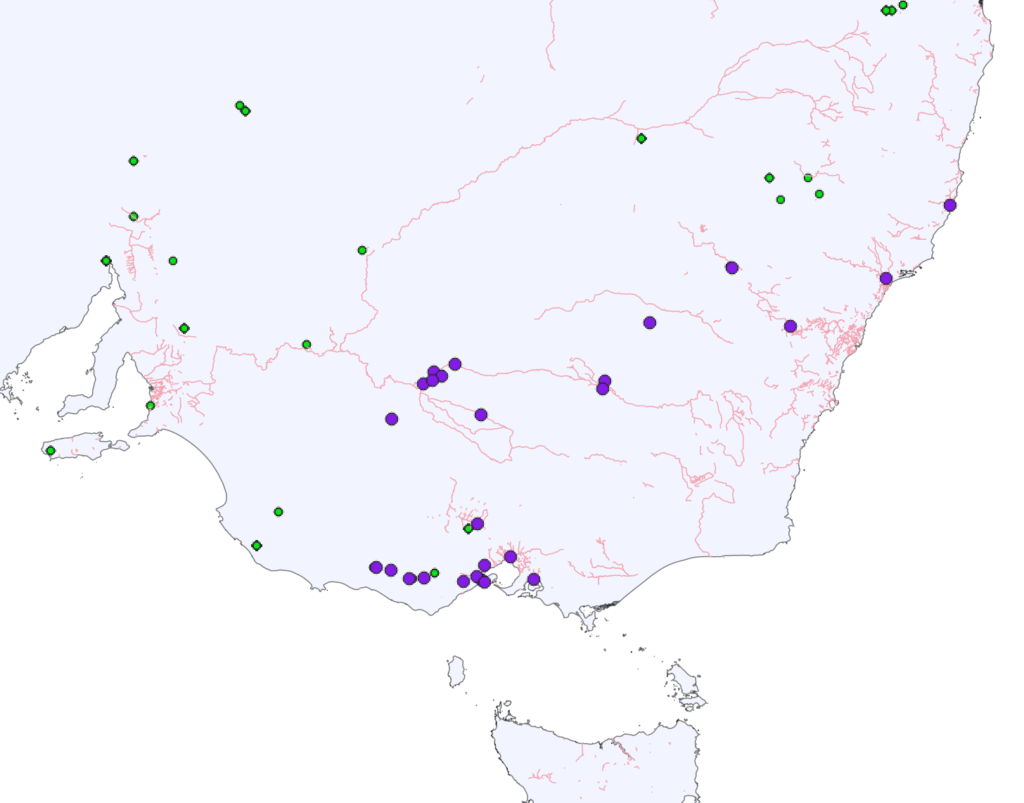

Looking beyond colonial stories for a moment, there have been suggestions that Aboriginal stories about bunyips in south-eastern Australia may be cultural memories of megafauna like Diprotodon. We can map Diprotodon finds in the region using the FosSahul palaeontological database.

But this is stretching the limits of what is useful. Palaeontological finds are always inevitably just a fraction of the story when considering the distribution of past species.

With all these experiments we also need to be careful not to look at correlation (or lack of correlation) and jump to conclusions.

When considering the Diprotodon example we need to be particularly careful. There has been a lot of speculation about potential connections between Aboriginal stories and historical or scientific knowledge. But it is not the place of historians or scientists to try to ‘prove’ or ‘disprove’ these stories using Western scientific measurements and observations. To do so is to oversimplify Indigenous narratives, and misunderstand the nature of both systems of knowledge.

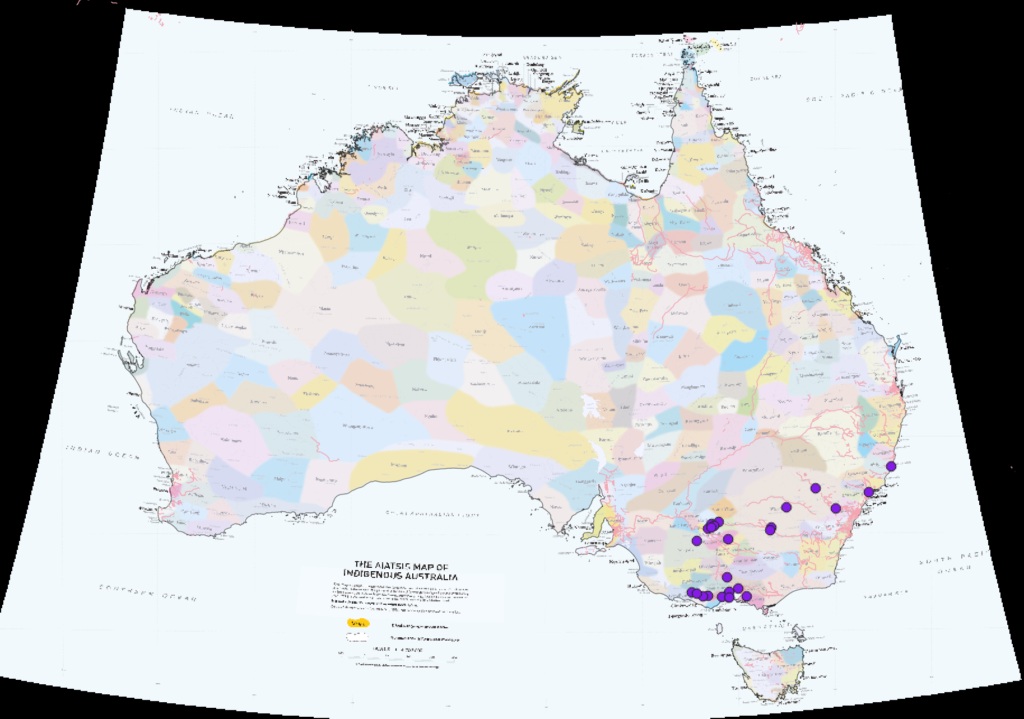

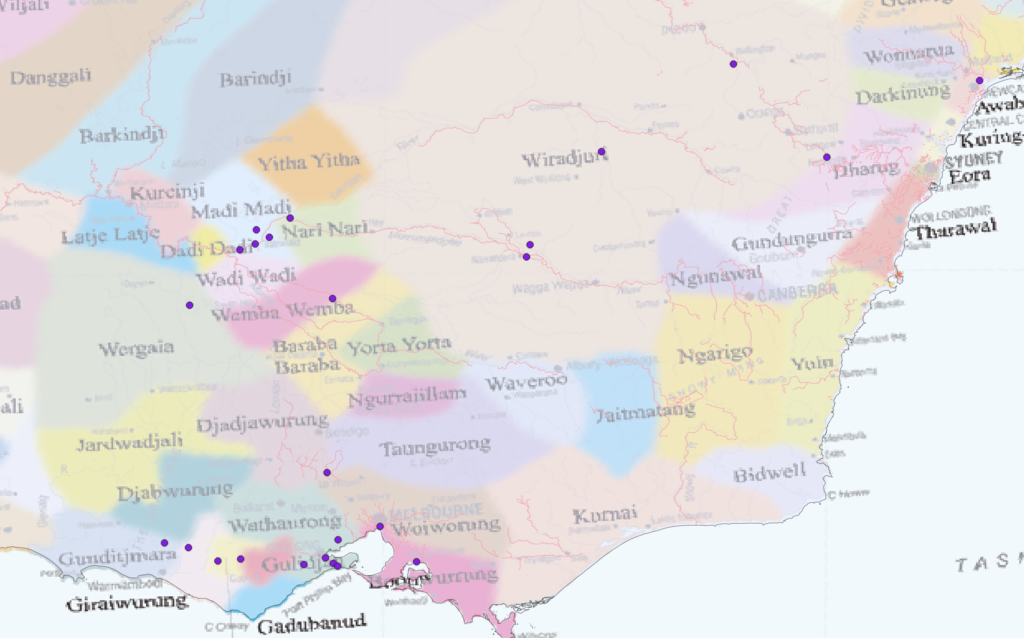

All of which is not to say we can’t use data to start asking particular questions. For example, an open question is the degree to which colonial stories of the bunyip are related to the stories of particular Aboriginal communities or language groups. Though the AIATSIS map is an imperfect tool, it is one way to think about identifying opportunities for collaborations in this area.

The Australian shape file and AIATSIS map are slightly different projections, so I had to skew the AIATSIS image. To achieve this, I used the technique for georeferencing historic maps covered in a recent HASS Geospatial workshop run by AURIN and Tinker.

Here are the results at a national level, to give an indication of the amount of transformation required.

And here is a closeup.

There are several locations related to bunyips in Wiradjuri country, and potentially interesting clusters on Madi Madi and Wathaurong lands. Given the limitations of the dataset these are very partial results, but further work may provide some useful pointers for working with communities—an essential next step for anyone really wanting to grapple with the entanglement of Indigenous and colonial stories of the bunyip.

Animation showing various map layers

Leave a Reply