As many of you will know I am interested in museum archives – how they are managed, stored, and documented in their own right, and how they are connected to other items and collections.

I’m also interested in archives and documents on display in museums. When managed by separate systems and processes (which seems to be the norm), it is often only when brought together with other things in display cases that archival connections and context become visible. I’ve been keeping an eye out for examples on my U.S. trip.

In my experience, documentary material is most often found in museums or displays focusing on social, cultural, political and biographical histories, which holds true here in America as much as it does in Australia. Writing of the latter, Tom Griffiths has suggested that “the first professional historians were archivists, nineteenth-century managers of the document”[1], and the continued prominence of the written document as a source displayed alongside non-textual objects is a feature of historical displays in many institutions.

Later, Griffiths states:

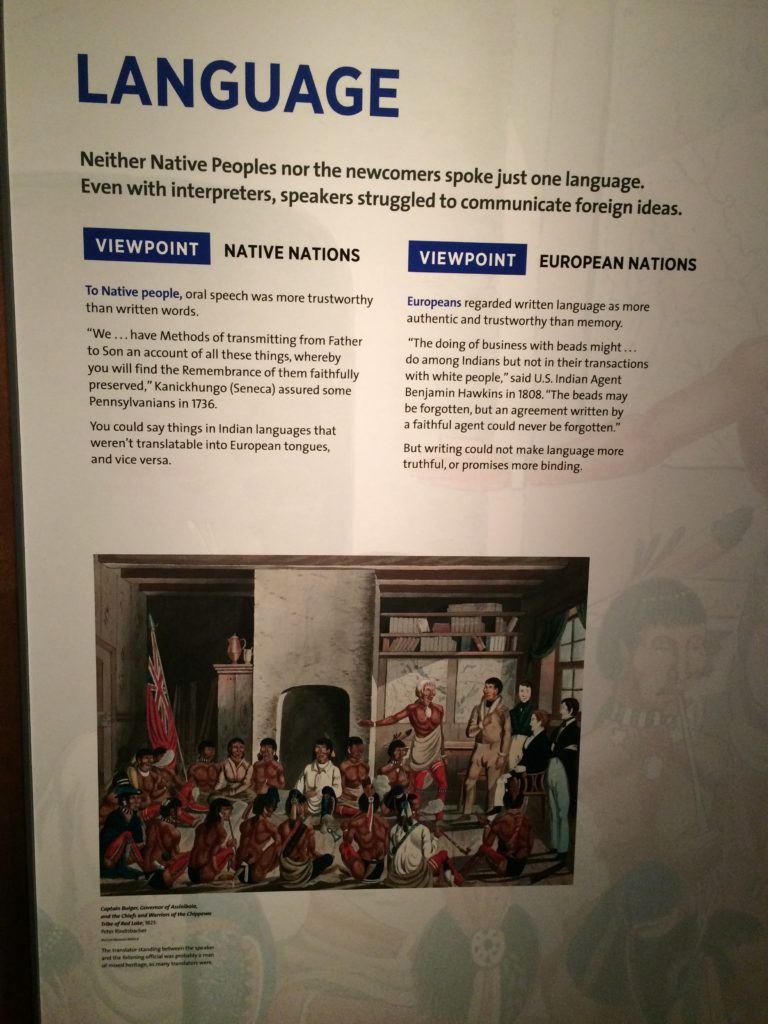

Professional history was founded on the distinction between oral and literate cultures, and between memory and history. Memory is fluid and personal, whereas history is a collective and public activity that requires verifiable sources and institutions for its transmission. [2]

The beautiful National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. explicitly addresses this divide.

While oral traditions may be seen as a contributing factor to the lack of documentary material in anthropological and ethnographic displays, Griffiths argues that it is also due to anthropology’s pursuit of scientific credibility, seeking the synchronic rather than the historical and focusing on the artefact rather than the text.

In keeping with this view of science, archives and documentary records often all but disappear in natural history museums and exhibitions (specimen tags aside), with two exceptions.

The first is not surprising. Sometimes a visitor will encounter displays which, though related to natural history, are more about individuals or events. The American Museum of Natural History’s display about Lincoln Ellsworth and the first flights across the Arctic and the Antarctic is an example. Suddenly in the midst of a museum almost devoid of visible archives we have a display with a historical focus, and with that focus comes log books, diaries, maps and other documentary material.

The second area is perhaps more surprising: paleontology.

It’ s something I discovered at three different museums on this trip, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles (NHMLA), the La Brea Tar Pits & Museum, also in L.A., and the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) in Washington, D.C.

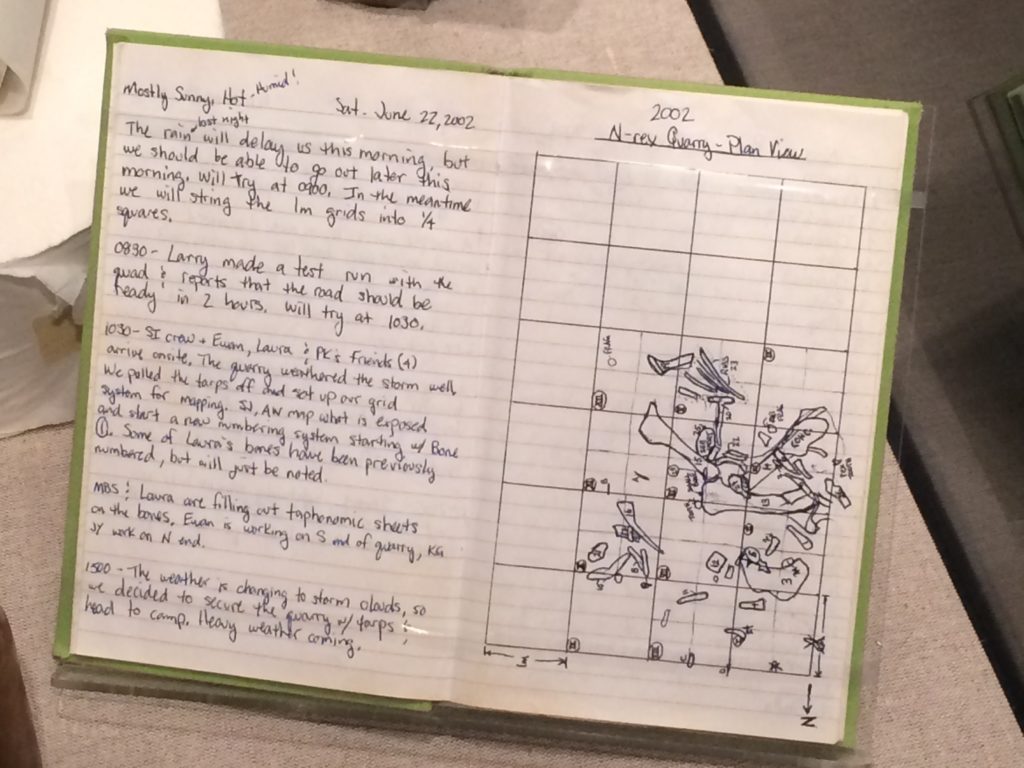

Taking them in reverse order, though the main dinosaur halls at NMNH are closed for refurbishment they have some impressive material on temporary display elsewhere in the museum. Included is a visible fossil lab with staff working on items brought in from digs, a video where the notebook is described as one of the key tools of the palaeontologist, and an actual field notebook on display alongside other equipment.

La Brea also includes a visible fossil lab and a section devoted to process.

Two wall cases start with the dig and documentation in the field and go through to cataloguing, research and a final publication, all illustrated with photographs and examples. These are between the open lab and a window looking in on a section of visible ‘back of house’ storage.

The second case includes the following text:

Even more important than the fossil itself is the information about where it was collected, because without that information, there is no way to fit the specimen into the ever expanding knowledge of ancient life on Earth. Paleontologists are constantly saddened by the well-meaning but uninformed amateurs who bring in fossils of rare or unknown animals without accurate locality information. Museums carefully record and save all of the known information about every fossil in their collections with either a written or a computerized catalogue system.

Leaving aside the slightly disdainful tone, the difference between an amateur and a professional, according to La Brea, is not in the specimens, it’s in the documentation.

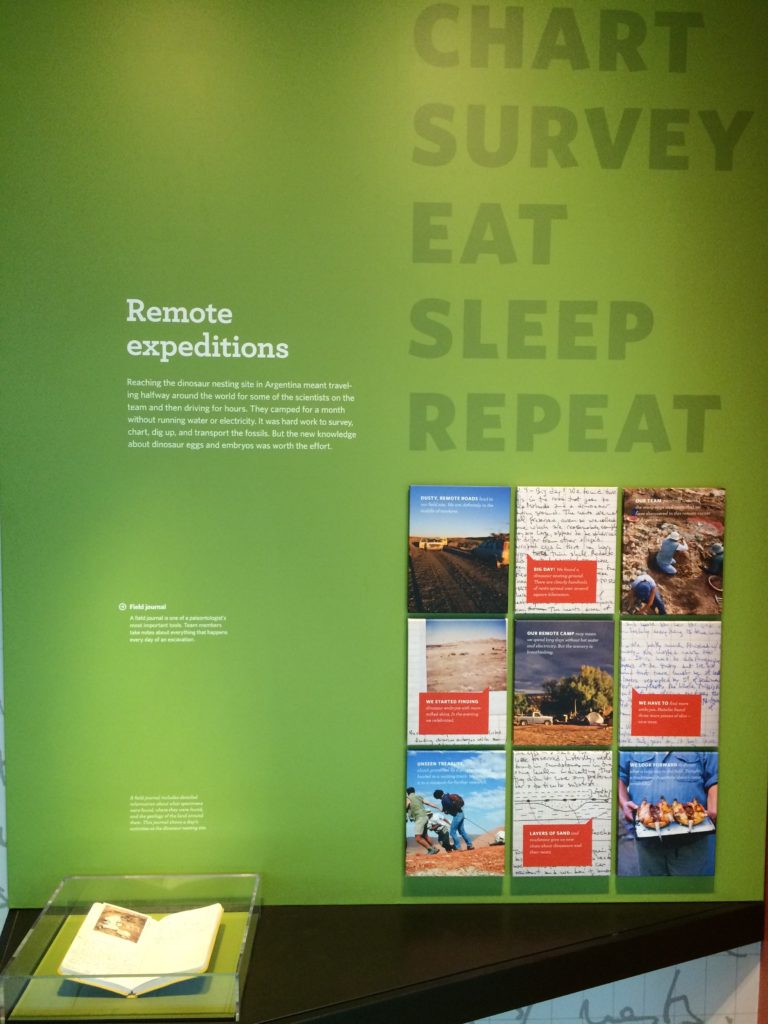

The place that started this journey was the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, and their display remains a highlight. On a long wall all about process and fieldwork there is a field journal on display, alongside extracts from several other journals to illustrate the sorts of information they contain.

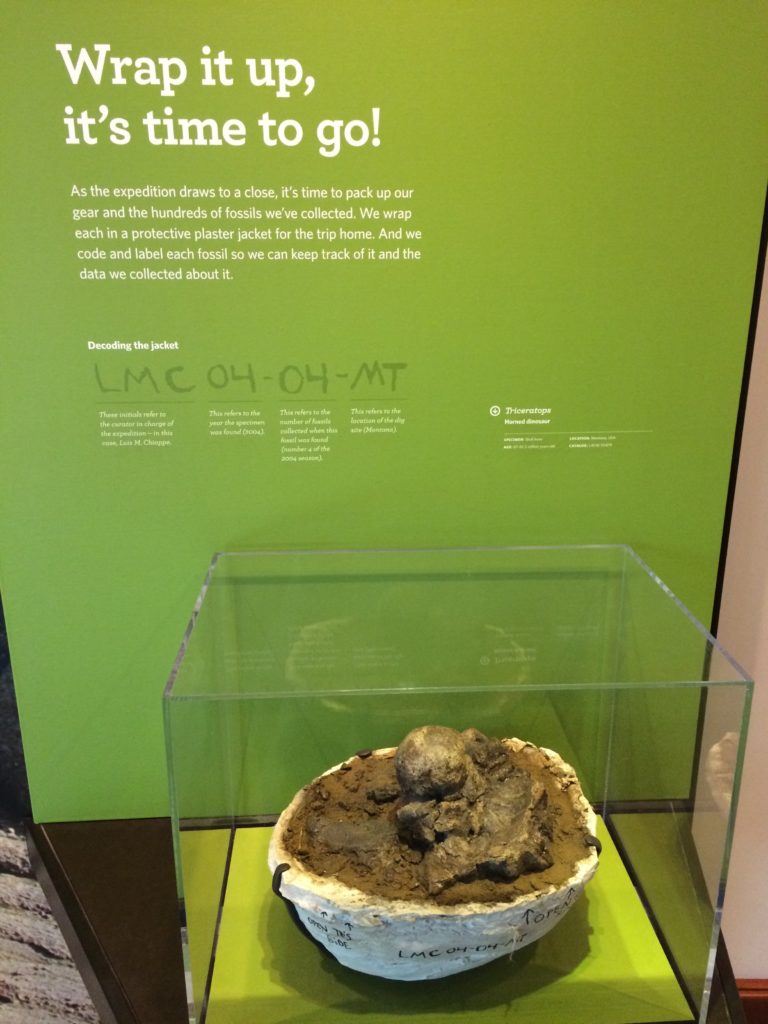

And on the same wall is an example of the method by which fossils are encased in plaster in the field, along with wall text explaining the structure and meaning of the unique identifiers used to track each package and the data with which it is associated.

The significance of these moments should not be overstated. These are large institutions, and the fact that there are a small number of field notebooks and other paperwork on display is far from an explosion of archives and historicism in the halls of natural history.

But the fact all these examples are from paleontology stands out; the discipline is visibly and repeatedly revealing its processes and practices to the public. In addition to field notebooks and open fossil labs there are videos, information about how artists’ renderings are developed, and explicit discussion of the disagreements, debates and changing beliefs about dinosaurs and other extinct animals.

Maybe it’s the Jurassic Park effect that makes paleontologists confident the public is interested in how they work as well as what they find. Whatever the reason, other disciplines in these museums don’t seem to share this belief. In not revealing their documentation, processes and debates, the science behind most natural sciences remains invisible to the general public.

In this area, as in so many others, dinosaurs rule the natural history museum.

[1] Tom Griffiths, Hunters and Collectors: the antiquarian imagination in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; Melbourne, 1996, p. 26.

[2] ibid., 196.

April 25, 2016 at 7:39 pm

Cheers Mike! I’ve been enjoying your posts on your US trip.

This one brought to mind a museum experience I had some time ago (around 2000?) in the “Armored Train” museum in the central Cuban city of Santa Clara. It really struck me at the time and made me think about the role of documentary exhibits in providing context and how they can radically change and deepen the visitor experience.

The museum is, strangely enough, housed in a series of armored railway carriages in Santa Clara, the capital of Las Villas province. It commemorates a battle that took place there at the end of 1959; the decisive, final, battle of the revolutionary war. A rebel column commanded by Che Guevara mounted a lightning campaign to capture the province and surround and then capture the capital, thereby cutting the island in two. That strategic defeat led immediately to the complete collapse of the regime.

In attempt to repel the rebel advance, and retake Santa Clara, the dictator Batista sent an armored train from Havana, loaded with hundreds of troops and all manner of weapons and ammunition (including anti-aircraft artillery). However, the rebels ambushed the train, derailed it (using a bulldozer), and quickly forced the troops inside to surrender. In a way the armored train itself was the last throw of the dice for Batista.

So the museum is right there on the spot. The bulldozer is there, on a concrete plinth. There’s a sculpture dedicated to el Che, and there are the big armored railway carriages housing the exhibits, each with a museum security person inside, like a railway conductor.

It was an interesting little museum, and I remember looking at various exhibits in one of the carriages (which included examples of the captured weapons, and the improvised bombs the rebels had used). Finally I noticed a small framed document hanging on the wall, without much drawing attention to it. It really looked like it might have been just a bit of commentary or a description of an object, but there was no object underneath it. On inspection it turned out to be by far the most interesting exhibit in the entire museum. It was a typed letter, addressed to Che Guevara, sent by an underground cell of the Communist Party at the Havana railway workshops. Immediately I was thinking “Really? Communists in a railway workshop? Whoever heard of such a thing?” and sure enough the letter spilled the beans in detail; describing the train, its schedule, passengers, and freight.

I noticed the guard watching me and I commented what an amazing document it was; that it was the most important exhibit there because it had basically guaranteed that the train would fall easily into the rebels’ hands. She replied that yes it was a crucial exhibit but that almost all the museum visitors passed it by without a glance. Which I thought was just weird! Would it have hurt them to maybe draw a bit more attention to the letter?! Because not only was it crucial to understanding the capture of the train, but it also carried a much more general lesson about the basis for the revolution’s triumph: it wasn’t just Fidel’s charisma or Che’s tactical brilliance, or the rebel army’s audacity and bravery, it was because they were part of a national revolutionary movement that included the urban underground.

April 29, 2016 at 3:51 pm

Thanks for this great story Conal! This sort of contextual information that documents in museums (or related to museum collections) is so valuable, and your experience really shows why. It’s also a really good example of why curators and exhibition designers should talk to their security guards – the people who spend hours in the space, watching visitor behaviour. They notice a lot.

July 12, 2016 at 9:37 am

The example of: Wall text – National Museum of the American Indian – is fantastic Michael.

There is sooo much buried in this.

Most recently, I have been interested to follow the work of Lynne Kelly. See a recent blog and the claim that some monuments are possibly used primarily as a memory space. The context is pre-literate cultures here, but the knowledge systems are remarkable.

http://www.lynnekelly.com.au/2016/07/castlerigg-stone-circle-cumbria/